Summary report on improving disabled people's exercise of legal capacity

- Download Summary Report as Word file [DOCX, 1.1 MB]

- Download Summary Report as PDF File [PDF, 148 KB]

- Executive summary

- Background

- Work on legal capacity issues for disabled people has been a priority for the Office for Disability Issues

- Next steps will focus on how people with coginitive impairment experience decision making

- Appendix 1 - Summary - Informal roundtable discussion: what's next for disabled people's exercise of legal capacity

- Appendix 2 - ODI thinking on legal capacity issues distributed to the roundtable participants

- Appendix 3 - What is the population impacted by support for the exercise of legal capacity?

Executive summary

1 Disabled people and their families say that what they want most is to have equal opportunities to live a good life, over which they have choice and control. This issue has been consistent over the years, most recently in public consultation during 2016 that informed the revision of the New Zealand Disability Strategy.

2 For many disabled people, there are more opportunities available in New Zealand today than there has ever been. However, for some disabled people, particularly those with a cognitive impairment, persistent barriers exist limiting their ability to have choice and control over their lives. These barriers include:

- negative stigma regarding cognitive impairment and the view that they are less-than-human, not capable of making decisions, and only needing care and protection

- the lack of timely, appropriate and specific support to individuals to help with decision making

- measures embedded in legislation that reflect an out-dated imperative to protect people with cognitive impairment that does not recognise their ability to make decisions with support.

3 The number of people with cognitive impairments is increasing, mainly due to the impact of an ageing population and the increase in people with dementia. This growth will place increasing pressure on current mechanisms, with people often denied the opportunity for self-determination that could happen if they have appropriate support.

4 The move to individualised arrangements for disability support services, such as that being developed under the Enabling Good Lives approach, will add to the demand for more effective options and support for decision making.

5 Other countries have already taken action to modernise legislation and policy that is consistent with a rights-based approach to supporting disabled people to have choice and control over their lives. New Zealand is becoming out-of-step with comparable jurisdictions.

6 The Office for Disability Issues has been working with disability sector organisations and government agencies to promote and develop a shared understanding of modern decision making for people with cognitive impairment. This is an action in the Disability Action Plan.

7 Some people with cognitive impairment will only be able to make decisions with support, regardless of any environmental change or reasonable accommodation provided. It is this group that has been the focus of the Office for Disability Issues’ work.

8 Within the population of people with cognitive impairment we have identified that there are five broad subgroups which have varying experiences in making decisions.

9 The work has focussed on decision making by adults as the legislative, policy and practice settings with regards to children and young people are different to that of adults.

10 Next steps will involve examining the experience of people with cognitive impairment in making decisions and whether there is any difference between the subgroups. This will inform development of possible options to improve their ability to make decisions.

Background

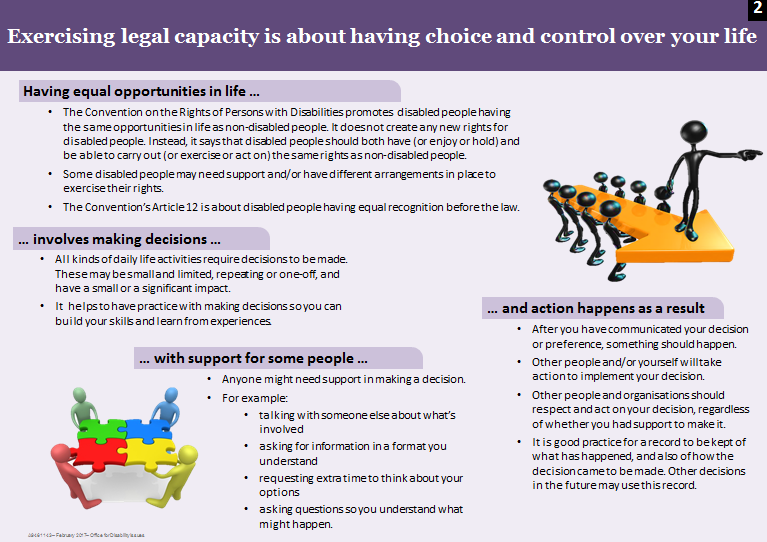

Having self-determination means being able to make choices about, and have control over, your life

1 A fundamental principle of international human rights law For example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 1 and Article 16 (For example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 1 and Article 16) is that all people are born with the same set of rights and with the same freedom for self-determination.

2 Self-determination is generally understood as being able to make choices and have control over your life – this involves decision making. A person’s ability to make decisions may depend on how other people respond to them and any relevant legislation, policy or practice.

Legal capacity means being able to act, and for your actions to be recognised as valid

3 The term “legal capacity” means an individual is able to act or make decisions in various situations and for the action to be recognised as lawful.

4 Situations may be formal and enabled in legislation, for example voting in elections for government, entering into a contract or will, or engaging in financial transactions.

5 Other less formal areas of action that a person may undertake in their daily lives include freedom of expression, choosing where you live, freedom of movement, or going to a medical appointment.

Disabled people may need support to overcome barriers to their decision making

6 For many disabled people, they may need support to overcome barriers to decision making such as by providing reasonable accommodation (for example, holding a meeting in a quiet office space) or ensuring changes in their environment (for example, making information accessible for blind people). Some people may just need extra time to help them understand what is going on and/or to process information they have just been told.

7 Negative attitudes towards disabled people can be as much of a barrier as physical ones. For example, where professionals or other people in a disabled person’s life do not consider it worthwhile, or do not make accommodations in providing information for a disabled person, then the opportunity for a disabled person to make decisions for themselves and/or communicate their decisions are compromised.

8 Through any difficulty in overcoming barriers, however, the disabled person retains autonomy over their decision making.

Some people must have support to make decisions

9 There is a smaller population of disabled people, however, who are not able to independently make decisions even with reasonable accommodation or environmental changes. This population is dependent on support being available so they can make decisions or express their preferences for decision making. In other words, their decision making is shared with one or more people supporting them.

10 This scenario has been described as demonstrating shared or relational autonomy. It is also more commonly referred to as “supported decision making”. In other words, the presence of support extends a person’s ability for decision making.

11 It is important to be clear that supported decision making is different from “support for decision making”, which may apply to anyone including disabled people (as we often make decisions by consulting with others). This distinction does not reduce the requirement in the UNCRPD, however, to ensure support is provided to any disabled people so they can exercise their legal capacity.

12 A person whose communication is limited or non-intentional will need other people, who know and understand them, to interpret their preferences and build decision making.

13 For some people, their physical environment may have an impact on their decision making ability. This means that a person may feel more able to make decisions or express their preferences if they are in a location they know and feel comfortable being in (and are less stressed) compared to a location where they are not comfortable.

14 There are extreme cases, such as with people in persistent vegetative states, who are unable to make any kind of communication or expression. This group of people will need 100 percent support so that decision making can happen. While this may look like substitute decision making, in practice the difference is that decision making by others must be based in what is known about the person needing support and their past experiences and preferences. Views of other people who know the person needing support may also be taken into account.

The target population has some kind of cognitive impairment

15 The population who are wholly or partly dependent on support to make decisions have in common an experience of some kind of cognitive impairment.

16 It is this population that has been the target of work by the Office for Disability Issues. This is because existing legislation, policy and practice does not necessarily recognise shared or supported decision making. Instead, people may become subject to coercive legal mechanisms intended to protect them from harm but which, in fact, limit or deny their right to make decisions about themselves.

17 In this context, people with cognitive impairment can be broadly described as having difficulty in:

- understanding the nature of decisions about matters relating to their personal care and welfare, or property

- foreseeing the consequences of decisions about matters relating to their personal care and welfare, or property, or of any failure to make such decisions

- communicating decisions about those matters.

18 This population of people with cognitive impairment can itself be broken down into five broad segments based on the origin and nature of the impairment:

- people with dementia (which by definition is a progressive deterioration of cognitive functioning with a gradual decline in independent decision making)

- people with acquired brain injuries (whether caused by injury or other event such as a stroke, where some rehabilitation of functioning may be possible)

- people with neurodisabilities (present since birth and having a life-long impact, including people with autism, people with intellectual disabilities, or Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders among others)

- people with mental illness (which may have variable impact on decision making and not necessarily be predictable, and the impact may come-and-go)

- people with other kinds of physical impairment or health condition affecting their communication and/or decision making abilities.

19 The experience of a person with a cognitive impairment in exercising their legal capacity may differ depending on when they acquired the impairment, and whether they have any other impairments.

People with cognitive impairment have experienced limits on, and denial of, their self-determination

20 Through history, people with cognitive impairment have been treated as having a lesser status than other people, due to perceived difficulties (or differences) that they have with thinking or learning.

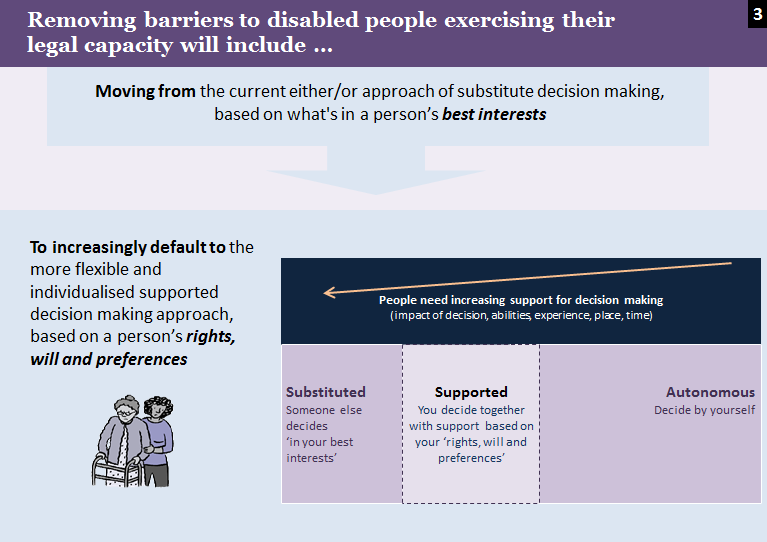

21 As a result, our systems and approaches have assumed that other people were needed to take over and make decisions in the best interests of the person with cognitive impairment. This is known as substitute decision making[1].

22 The formalisation of substitute decision making has evolved through legislation and the courts over time, originally motivated by the Crown’s parens patrie responsibilities[2] that the person with cognitive impairment should not be taken advantage of and is kept safe for their own good.

23 Disability organisations in New Zealand have identified that, in some cases, it is possible that a person under substitute decision making can end up with no say on what happens to them. In their view, a lot of power resides in the substitute decision maker, with minimal safeguards available and limited monitoring by the courts.

24 Advocates for changing substitute decision making regimes argue it is time to restore rights to people with cognitive impairment, on an equal basis with others, while not lessening any safeguards available for them.

[1] Some commentators (such as Professor Gerard Quinn from Ireland) have said that people under substitute decision making experience “civil death”, with no or little rights compared with other people. This has been compared to the situations in history of prisoners, slaves, or married women.

[2] This has been broadly described as a responsibility of the Crown “to take care of those who are not able to take care of themselves” - principally persons of unsound mind and children. (Joseph, Rosara. "Inherent jurisdiction and inherent powers in New Zealand" [2005] CanterLawRw 10; (2005) 11 Canterbury Law Review 220). Also, the High Court retains such general powers as provided in the Senior Courts Act 2016, section 14: Jurisdiction in relation to persons who lack competence to manage their affairs.

Self-determination is a key right in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

25 The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) expresses self-determination throughout its Articles. It is particularly strong in Article 12: Equal recognition before the law. This Article sets out specifically[3] that disabled people have:

- the right to equal recognition before the law

- the right to enjoy legal capacity (that is to be a person who is recognised as capable of acting under the law)

- the right to exercise their legal capacity (that is to be a person who is able to make decisions and take action to implement decisions or see that implementation happens, also known as having legal agency)

- the right to access support to exercise their legal capacity

- safeguarding to protect their rights and prevent abuse and undue influence from the provision of support

- financial and property rights.

[3] While there were no new rights introduced in the UNCRPD, its specification of what needs to happen so that disabled people can experience the same rights as others has, in some cases, created new requirements on the State.

26 The rights in Article 12 are often considered to be fundamental to all other rights in the UNCRPD. This is because it is about being treated as a person with the same rights as others and having the ability to take action about those rights.

27 Implementation of Article 12 requires a paradigm shift from substitute decision making (based on what another person considers is in the best interests of a person with cognitive impairment) to supported decision making (being based on the person with cognitive impairment’s rights, will and preference).

28 This shift means that rather than asking “What do I think the decision should be for the person with cognitive impairment?”, the question instead becomes “What does the person with cognitive impairment want this decision to be, based on the preferences they have expressed and what I know about their previous preferences?”

29 The shift would place the person with cognitive impairment at the centre of decision making about them, in a context of support related to their individual needs and abilities.

Implementation of Article 12 is a priority[4] for the United Nations

30 The UNCRPD Committee will be looking for State Parties to demonstrate in their reviews compliance with Article 12. Key indicators of success include:

- There should not be any legislation or policy that limits, on an equal basis with others, a person’s decision making rights or ability to act on the basis of cognitive impairment or any other impairment.

- If needed, support should be provided to help decision making or taking action based on a person’s rights, will and preferences.

- Safeguards should be in place so that a person needing support to make decisions or take action is protected from abuse or undue influence by other people.

31 As a State Party to the UNCRPD, New Zealand is required to participate in a review of its implementation every four years by the UNCRPD Committee.

32 The UNCRPD Committee’s Concluding Observations of the 2014 review included the following:

18. The Committee recommends that the State party take immediate steps to revise the relevant laws and replace substituted decision-making with supported decision-making. This should provide a wide range of measures that respect the person’s autonomy, will and preferences, and is in full conformity with article 12 of the Convention, including with respect to the individual’s right, in his or her own capacity, to give and withdraw informed consent, in particular for medical treatment, to access justice, to marry, and to work, among other things, consistent with the Committee’s general comment No. 1 (2014) on equal recognition before the law (refer paragraph 22).

33 In 2015, the Government response to the Concluding Observations noted:

There is already an action in the Disability Action Plan 2014-2018 to ‘Ensure disabled people can exercise their legal capacity, including through recognition of supported decision making’ [led by the Office for Disability Issues]. This work may recommend changes to legislation, however no decisions have been made yet. Legislative provisions for non-consensual assessment and treatment may be necessary to treat severe mental illness where an individual may not be capable of giving or communicating informed consent to medical treatment.

34 The second review by the UNCRPD Committee is expected to begin in 2018, with a List of Issues to be provided seeking a Government response. It is expected that the UNCRPD Committee will have a particular interest in following up on its previous Concluding Observations.

35 As part of the review, the New Zealand Government will need to appear before the UNCRPD Committee sometime from 2019.

Work on legal capacity issues for disabled people has been a priority for the Office for Disability Issues

36 In 2014, the new Disability Action Plan included an action on legal capacity issues for disabled people “Ensure disabled people can exercise their legal capacity, including through recognition of supported decision making”. This action contributes to the New Zealand Disability Strategy 2016-2026 outcome: choice and control, “We have choice and control over our lives”.

We have focused on stakeholder engagement to build awareness

37 Implementing this action has started with a focus on promoting and developing a shared understanding on legal capacity issues that is consistent with the UNCRPD.

38 This approach was chosen because of the complex nature of legal capacity issues. To ensure that any conversations about making changes domestically were consistent with the UNCRPD and reflect the lived experiences of people with cognitive impairment, we focused on knowledge building.

39 While we were aware that legal capacity issues had been raised over time by people from the learning/intellectual disabilities sector, there did not appear to have been any similar discussion or identification of legal capacity issues by other impairment sectors.

40 In response, we engaged with other stakeholders, particularly those involved with people with dementia and people with mental illness, to understand how legal capacity issues are experienced differently by different population groups.

41 A key event was a two-day hui[5] held in Auckland, in April 2016, that brought together around 140 people from across a range of stakeholders to share practice and understanding of legal capacity issues.

Footnote

[5] The hui was initiated by the Office for Disability Issues, which also contributed the majority of funding. Auckland Disability Law agreed to organise the hui, reflecting their interest in the subject and existing networks in the disability sector. The hui was also supported by the Human Rights Commission, People First New Zealand, and Te Roopu Taurima.

42 The hui was successful in achieving the following outcomes:

- It helped to bring together stakeholders representing different populations, which may not have seen each other as allies (particularly those representing people with learning/intellectual disabilities, people who are non-verbal, and people with dementia).

- It identified an issue in common that different impairment sectors could support, even though it manifests differently.

- It fed into some resources being produced providing information about supported decision making, which were published by Auckland Disability Law and have proved very popular and useful.

43 In 2016, the Office for Disability Issues also commissioned the Donald Beasley Institute to undertake a literature review on current practice and experiences on support for disabled people to exercise their legal capacity. The literature review was published in October 2016. It has been a helpful addition to the discourse in New Zealand on legal capacity issues for disabled people.

44 In February 2017, we hosted an informal roundtable involving a small number of stakeholders that are active in the legal capacity space so that everyone could update each on work priorities and to share concerns. A summary of the roundtable discussion is available in appendix 1. A presentation shared at the roundtable that shows the Office for Disability Issues’ understanding of legal capacity issues impacting on disabled people is in appendix 2.

45 As well as those disability sector organisations present, the Office of the Ombudsman and the Human Rights Commission are particularly keen to see reform regarding legal capacity issues. This interest is shared by the Ministry of Health.

We have examined the population of people with cognitive impairment

46 As a second step, we have sought to understand in more depth the characteristics of the population impacted on by legal capacity issues. This will also be useful in enabling future application of a social investment approach.

47 It is difficult to estimate the number of people that may currently experience problems with decision making. For some people, this is because their abilities may fluctuate depending on the nature of the decision, their environment, whether or not the right support is available to help them, the time of day, and anything else happening in their life that may cause stress and be distracting.

48 Another difficulty is that in any group of people defined by their impairment, there will be a range of abilities from mild to significant. Only people with significant impairment will likely be reliant on support to enable their independent decision making (that is, supported decision making is necessary for the disabled person to make decisions or express their preferences for decisions). Our brief scan of data identified that it was not always straightforward to separate out levels of impairment.

49 Some people may have multiple impairments. This makes it challenging to estimate the size of the overall population of unique individuals. Where a person has multiple impairments, they may face added and compounding barriers to decision making compared with other people with impairments. More support may be required to ensure people with multiple impairments have equal opportunities in decision making as others.

50 On the basis of our consultation to date, we consider that the population of people with cognitive impairment who are impacted to a greater or lesser extent by legal capacity issues can be broken down into the following five groups (see Appendix 3):

- People with dementia (which by definition is a progressive deterioration of cognitive functioning with gradual decline in independent decision making), currently experienced by an estimated 62,000 people.

- People with acquired brain injuries (whether caused by injury or other event such as a stroke, where some rehabilitation of functioning may be possible), currently experienced by an estimated 72,000 people.

- People with neurodisabilities (present since birth and having a life-long impact, including people with autism, people with intellectual disabilities, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders among others), currently experienced by an estimated 194,000 people.

- People with mental illness (which may be variable in impact and not necessarily predictable). This is a difficult group to estimate having diminished decision making abilities (for instance, people with serious mental illness may be likely considered as subject to either compulsory assessment or compulsory treatment under the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992. In 2015, around 162,200 New Zealanders (3.5% of the population) accessed specialist mental health services and of those 9,906 (6.5%) were subject to the compulsory provisions of the Act.

- People with other kinds of physical impairment or health condition affecting their communication and/or decision making abilities. This is also a difficult group to estimate (For example, there are 7,000 people with Cerebal Palsy who may be included; and there are 145,000 people who have difficulty in speaking and being understood).

51 Using this information, we can assume that the population of people who may need support for decision making and/or who may experience increased choice and control from having better support arrangements may range from the tens of thousands to around a hundred thousand people.

52 People who would benefit from supported decision making would be a smaller subset of this population.

We have provided advice to other government agencies on legal capacity issues

53 The Office for Disability Issues has used opportunities to promote attention to legal capacity issues affecting disabled people in our advice to other government agencies’ policy development. It is a subject matter with particular relevance to improvements to safeguarding measures regarding disabled people experiencing violence and abuse.

54 The Ministry of Health has been leading the recognition of legal capacity issues throughout its work, for example as demonstrated in its July 2017 Cabinet paper: Disability Support System Transformation Proposed High Level Design and Next Steps.

Next steps will focus on how people with cognitive impairment experience decision making

55 Based on our work to date, the Office for Disability Issues intends to do further work to understand how the population of people with impairment experience decision making in the following areas:

- legislation/policy – what is the mandate or direction impacting on supported decision making?

- practice – what does decision making look like in a person’s ordinary life?

- education/information provision – what resources might be needed to promote a positive shift in attitudes towards supported decision making?

56 We assume that the population subgroups may have different experiences due to the nature of their impairment and any associated negative stigma affecting other people’s attitudes towards them.

57 This work may helpfully inform a social investment approach orientated at improving people with cognitive impairment’s experience with decision making.

Appendix 1: Summary – Informal roundtable discussion: what’s next for disabled people’s exercise of legal capacity

1 An informal roundtable meeting was held on 20 February 2017, at the Ministry of Social Development, Wellington.

Purpose

2 The Office for Disability Issues organised a roundtable discussion as an opportunity for key organisations that are leading work promoting disabled people’s exercise of legal capacity, or that have an active interest, to come together to:

- share current or planned work, so there was common knowledge of activity in the space

- update on current issues and concerns impacting on disabled people’s exercise of legal capacity.

3 Organisations and people participating in the roundtable are appended.

4 The Office for Disability Issues acknowledges that there is a wider range of stakeholders working and/or interested in the legal capacity space. The roundtable was intended to capture a snapshot of activity and views of a few key representative stakeholders, but not everyone or every viewpoint.

Context

5 The Office for Disability Issues has had an interest in legal capacity issues for some time. It is a challenging and difficult area. However, it impacts the most on those more vulnerable people:

- who are not always able to speak up for themselves; and/or

- who are viewed by other people as not being able to speak up and be heard; and/or

- who are significantly dependent on support.

6 The issue of supporting disabled people’s exercise of legal capacity has been described as ‘rocket science’ by one researcher. We think that more people should be talking about legal capacity issues for disabled people, so that the subject can be more widely understood and acted on.

7 Underlying discussions on support for disabled people’s exercise of legal capacity, however, is a real tension between promoting the autonomy of a person and ensuring safeguards are in place to protect them from undue influence or abuse.

8 The Office for Disability Issues has recognised the importance of clarifying terms used in discussions. Two key terms are:

- Legal capacity (or recognition as a person before the law, who holds rights and can exercise them) impacting on disabled people.

- Legal agency to exercise legal capacity (or recognition of support for decision making, including legitimising supported decision making).

9 It can often be the case that everything is collapsed down to ‘supported decision making’. However, there are real differences between the two areas of legal capacity and legal agency and it pays to be intentional in use of language to determine what you are talking about.

10 It has also been useful to clarify the difference between:

- ‘support for decision making’, which can apply to anyone

- ‘supported decision making’, which involves shared action by the decision maker and at least one other person; and without the support, the decision maker would not be able to make decisions (that is the decision maker is dependent on support to make decisions or to express their will and preferences).

11 The Office for Disability Issues continues to promote discussion towards a shared understanding of what support for disabled people to exercise their legal capacity means for New Zealand.

Sharing work done or work coming up (as at February 2017)

| Organisation | Work done | Work coming up |

| Ministry of Justice |

|

|

| IHC Advocacy |

|

|

| Dementia Cooperative |

|

|

| Donald Beasley Institute |

|

|

| Ministry of Health |

|

|

| Convention Coalition Monitoring Group |

|

|

| Age Concern NZ |

|

|

| Ministry of Social Development |

|

|

| Office of the Ombudsman |

|

|

| Human Rights Commission |

|

|

| Office for Seniors |

|

|

| Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner |

|

|

| Disabled People’s Assembly |

|

|

| People First |

|

|

| Complex Care |

|

|

| Auckland Disability Law |

|

|

| Office for Disability Issues |

|

Open discussion on issues or areas of concern

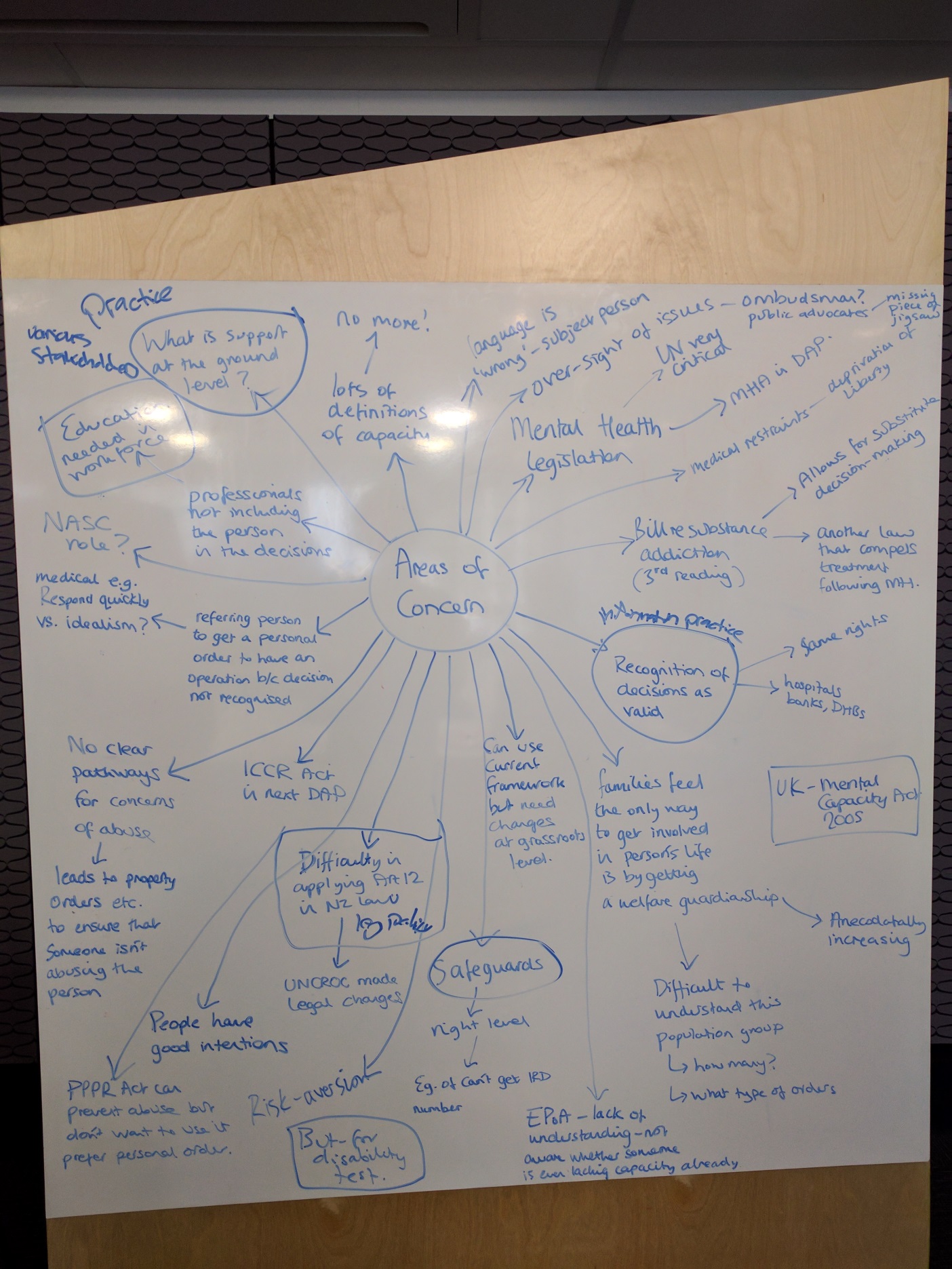

The image above shows a map of the areas of concern raised. Following is the text in the image, starting from the top left hand side and moving around the board anti-clockwise.

- What is support at the ground level?

- Lots of definitions of capacity – no more!

- Professionals not including the person in the decision making – education needed for workforce.

- NASC role?

- Referring person to get a personal order to have an operation because decision no recognised – medical eg respond quickly vs ideally have time to discussion/get support.

- IDCCR Act needs examining.

- No clear pathways for concerns of abuse – leads to property orders etc to ensure that someone isn’t abusing the person/taking their money.

- Difficulty in applying Article 12 in New Zealand law and policy. – UNCROC led to legal changes.

- People have good intentions

- PPPR Act can prevent abuse but don’t want to use it, prefer personal order.

- Risk aversion.

- Can use current framework, but need changes at grass roots level.

- Safeguards – right level – eg can’t get Inland Revenue number.

- Enduring Power of Attorney – lack of understanding, not aware whether someone is lacking capacity already.

- Language is wrong – subject person.

- Oversight of issues – Ombudsman? Public Advocate introduced (missing piece)

- Mental Health legislation – UN critical - Disability Action Plan looking at Mental Health Act.

- Medical restraints – deprivation of liberty.

- Bill change addictions and substances legislation – follows Mental Health legislation, compels treatment.

- Information and practice – recognition of decisions as valid – same rights, hospitals, banks

- Cf UK mental capacity act

- Families feel the only way to get involved in person’s life is by getting a welfare guardianship --- anecdotally, this is increasing.

- Difficult to understand this population group – how many? – what type of orders?

Questions raised during the open discussion

Note: the following list captures what was talked about during the meeting. It does not reflect any commitment or agreement by government agencies on the matters raised.

- Would it be useful to consider legal capacity issues in a policy framework: legislation/policy; practice; and education/information provision?

Legislation or policy

- What alignment is there across government agencies, eg Ministry of Health’s Choice in Community Living, tenancy contracts for housing, evolving practice for children, Inland Revenue?

- How can the law be changed to have a greater balance between promoting autonomy and safeguards to protect a person?

- Is it time to seriously consider an independent advocacy service for New Zealand similar to that existing overseas?

- Is it time for the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act to move from the justice space to instead be administered in the health/welfare space, given the need to promote support as well as safeguards for a person?

- What would it take to extend the role of the mental health inspectors into the legal capacity space, for example?

- What would a social investment approach look like applied to legal capacity issues? What would be needed for it to happen?

Practice

- How to get decisions made with support recognised and acted upon, such as by banks, district health boards, etc?

- Is the number of welfare guardians increasing? Who are the people over which welfare guardianship/other orders sought? What do we know about this population?

- What monitoring happens after a welfare guardian is appointed?

- Health treatment can be denied to people with intellectual disability because they are not considered able to give informed consent – how does this marry with duty of care?

- Academic theorising does not always translate to the experience of everyday living – how can the discussion move towards a more practical basis?

- What more can be learned from overseas, such as in the UK, on alternatives to substitute decision making or what needs to be demonstrated before substitute decision making is put in force?

- Can the Family Court make directions on how a subject person under a guardianship/other order should be involved in decision makings about themselves?

- What is the best way to record a person’s preferences, so that other people can interpret decisions and take action for them?

- How can the quality of support be monitored or assured? Not everyone has the skills or personal abilities to provide good quality support to someone. It is a skill.

- A person in a care setting may not be known by the staff to have a guardianship/other orders or enduring power of attorney. How can this information be better recorded and available to those people who may need to access it, for example healthcare services, Police?

- Why is there not mandatory reporting of abuse seen on an adult? Isn’t this the case with children?

- What can be done so that disabled people who do speak up and go to the Police or the Health and Disability Commissioner to make a complaint are heard and acted upon, and not treated as an ‘unreliable witness’ and their case not pursued?

- Is there any ability to share approaches or check in with each other on difficult cases, for example form a virtual peer network which would be particularly useful for ‘hard cases’?

Information, education, awareness raising

- Are there alternatives to avoid courts and use of lawyers and legal mechanisms of guardianship and personal orders, and avoid costs and stress involved? Why can’t there be a new way that puts the emphasis on support?

- How can people acting as a guardian, under an order, or an attorney under an activated enduring power of attorney be better informed and educated on their role, so they do not think they can do anything they want?

- How can a vulnerable person speak up and engage in a legal process, if they are limited by legal aid available and not being aware of how a court works?

- Is there a risk with a greater use of individualised funding, that people will become more isolated in the community and lose the protections that they may have had with their families or services?

- Should priority in this work be put toward older people, given their population is growing fast and there will be more of them?

- Can case stories be collected that show side-by-side what good looks like and what would be needed, in an alternative scenario, to get to good? This would be helpful to learn approaches practically.

Appendix 2: Office for Disability Issues thinking on legal capacity issues distributed to the roundtable participants

Appendix 3: What is the population impacted by support for the exercise of legal capacity?

This is a summary of a working document prepared to assist the breakdown and estimating of the size of the population of people who have some kind of cognitive impairment affecting their independent decision making (and therefore who may need support to assist their decision making/exercise of legal capacity). Further information on the impact on decision making and the reference sources is available on request.

Further work would be needed to get a more precise population estimate (if the data allowed). This report’s estimate may be sufficient, however, to inform further work. There may not be much more value gained from further consideration of the population.

Strategic context and mandate

- UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Article 12 – Equal recognition before the law.

- New Zealand Disability Strategy: Outcome 7 – Choice and Control. We have choice and control over our lives.

- Disability Action Plan: Action 7 A: Ensure disabled people can exercise their legal capacity, including through recognition of supported decision making.

- Legal capacity includes the capacity to be both a holder of rights (enjoy) and an actor under the law (exercise). To be a holder of rights entitles a person to full protection of his or her rights by the legal system.

- Legal agency is to act (exercise) under the law recognising a person as an agent with the power to engage in transactions and create, modify or end legal relationships.

Key terms definition

Reference: United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ‘General Comment No. 1 (2014): Article 12: Equal recognition before the law’.

Population segments estimate

| Broad characteristics in common is the impact on decision making |

|

The target population can be described generally as people who have some kind of cognitive impairment that affects their ability to independently:

|

Notes

- Some individuals have multiple impairments and may be counted more than once in the segments. Estimating a total potential unique population is not possible.

- Each segment will contain a range of need for support in decision making: from none to some to fully supported decision making necessary.

- Support is a dynamic continuum and depends on what an individual may need at any given time. Some impairments are volatile. For some people, their environment may impact on their decision making ability.

The following populations are identified as having these characteristics in common. This table is not an exhaustive list of all populations that may have difficulties with decision making.

| Segment characteristic | Sub-groups | Group size estimate |

| People with dementia (which by definition is a progressive deterioration of cognitive function with gradual decline in independent decision making ability) | - |

Estimated prevalence in New Zealand of 62,287 people with dementia.

|

| People with intellectual disability who develop dementia | The rate of occurrence of dementia among people with intellectual disabilities is about the same as in the general population (or about 6% of people age 60 and older). However, the rate among same-age adults with Down Syndrome is much higher - about 25% for adults age 40 and older and about 65% for adults age 60 and older. | |

| People with acquired brain injuries (such as resulting from an injury or stroke, which is acquired suddenly and affects a person’s ability to make decisions independently for a limited period or life-long; for some people, rehabilitation may improve their cognitive functioning) | People with injury-caused brain injury | Estimated prevalence in New Zealand of traumatic brain injury is 527,000 people. Of these people, there is a prevalence of 27,350 moderate to severe cases of traumatic brain injury. |

| People experiencing stroke | There are about 7,000 new strokes in New Zealand annually and some 45,000 New Zealanders live with the aftermath of stroke. One in four are younger than 65 years of age. [Health Research Council] | |

| People in persistent vegetative states |

A small proportion (estimated at 2.77%) of people experiencing severe traumatic brain injury may experience persistent vegetative states. Some survivors of severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) fail to fully recover self and environmental awareness despite awaking from acute coma. The term persistent vegetative state (PVS) is applied when the vegetative state (VS) lasts for at least 1 month…The overall prevalence of PVS at six months after injury was 2.77% [NeuroRehabilitation journal article] |

|

| People with neuro-disabilities (which exist from birth and have life-long impact, including people with autism, people with FASD (Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders), people with learning/intellectual disabilities) | People with intellectual disabilities |

There are 96,800 people with intellectual disabilities. Of these, there are 67,000 adults with intellectual disability. [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] |

| People with autism |

Estimated 40,000 to 65,000 New Zealanders with autism. [Office for Disability Issues, Autism New Zealand] |

|

| People with FASD (Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders) | Estimated 44,300 New Zealanders with FASD. [NZMA article] | |

| People with mental illness (such as when a person is in a disordered state (whether temporarily, intermittent or life-long) as well as due to negative attitudes of other people/professionals on their decision making abilities) | People with mental illness |

An estimated 5% of the New Zealand population (242,000 people) are living with long-term limitations in their daily activities as a result of the effects of psychological and/or psychiatric impairments. [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] In 2015, around 162,200 New Zealanders (3.5% of the population) accessed specialist mental health services and of those 9906 (6.5%) were subject to the compulsory provisions of the Mental Health Act. [Director of Mental Health's Annual Report 2016, Ministry of Health] |

| People with other kinds of physical impairment or health conditions affecting communication or independent decision making. | People with physical impairment with high support needs |

Having difficulty learning new things because of a long-term condition or medical problem affect 5% (242,000) of the total population. [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] Questions about memory loss were only asked of adults - 5% of the adult population (48,350) had ongoing difficulty with their ability to remember. This impairment type rises with age. 10% of people aged 65 or over were affected, compared with 5% of those aged 45 to 64, and 2% of those aged 15 to 44. [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] |

| People with Cerebral Palsy | Having difficulty speaking (and being understood) because of a long-term condition or medical problem affects 3% of the total population (145,200). [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] | |

| People who are non-verbal | Having difficulty speaking (and being understood) because of a long-term condition or medical problem affects 3% of the total population (145,200). [Statistics NZ: 2013 Disability Survey] | |

| People with Parkinson’s | This is currently around 1% of people above the age of 60 who have Parkinson’s. This equates to around 6000 people. As the condition advances, decision making increasingly becomes affected. | |

| People with Multiple sclerosis | Cognitive changes are common in people with MS—approximately 50% of people with MS will develop problems with cognition. |

Page last updated: